In the mythic past, November 1st marked the beginning of the Irish new year. The day was called Samhain (SAH-win), and on this day the liminal borders between the so-called real world and the otherworld flung open. Births, deaths, and all manner of changes were said to have occurred on this day. One scholar describes the day as “a partial return to primordial chaos…the appropriate setting for myths which symbolize the dissolution of established order as a prelude to its recreation in a new period of time.”1 This description rang bells in my head, for I have (only briefly) begun to look into medieval Irish eschatology, a theological theme with which the medieval Irish seem to have been particularly preoccupied. Putting the two ideas together, I’ve been asking myself if perhaps the medieval scribes writing about the wild tales surrounding Samhain did so out of a longing for something both primordial and eschatological: an ultimate re-birth.

According to Genesis, the world began as a primordial chaotic mass awaiting the hovering, nurturing tending of the Holy Spirit. Once order was cultivated from the chaos, it wasn’t long until that order was usurped by a New Undoing Order, one that brought all manner of death, pain, and suffering that continued to decay the original goodness and beauty of Creation. This trope is highly analogous to the ones we find in the stories surrounding Samhain, as well as the political and religious contexts of the manuscripts which recorded them. Perhaps these stories inspired the imaginations of medieval scribes, imaginations that had suckled on the beautifully radical transformations as promised by the theology they studied. Perhaps they found in these stories a kindred longing for a return to that original primordial chaos, to a prelapsarian state, but one that would be recreated into a new world of even greater beauty and wild wonder than even these mythological tales could describe.

November 1st is also a significant day in the liturgical calendar: All Saints Day. Among other things, the day is a memento mori, a reminder that not even the holiest among us are exempt from death. But when considered with Samhain, the reminder is that not only will we die, but that we await a re-birth, we await the re-creation to come after the wrongly established order of death is dissolved.

Oftentimes in the scholarly literature, the predominant assumption is that medieval authors were primarily motivated by political and ethnic issues when writing these texts. Maybe it’s just me, but I often throw up my hands in frustration over this trend amongst scholars. I too am an artist and an author, but one who hates the subject of politics with a passion. My own motivations and inspirations are more theologically inclined; even more basically, I am drawn to stories and art that simply move me to wonder over their beauty. Is it too simplistic to think that perhaps some of the medieval scribes were just like me? That, having grown weary of politics and the conflicts it brings, they instead escaped to imaginary worlds of beauty and wonder for the sheer joy of it, for the consolation it brings to their souls?

I would venture to say that somewhere in the medieval Ireland, there once sat a curious scribe who also found himself overwhelmed by the chaos of his world, and he sought consolation by filling his imagination with worlds and ideas that far overshadowed any one passing political moment. I’m taking it upon myself to continue that impulse in my own work, trying to first encounter each story as art written for the sake of wonder before assuming a critical posture that dissects a story so thoroughly that any joy to be had from it spilled out onto the floor long ago.

Curated Joys

A Book

This month’s collection of curated joys includes a new book by Sarah Clarkson titled Reclaiming Quiet: Cultivating a Life of Holy Attention. I had the privilege of working with Sarah to launch the book ahead of its release on November 5th, and I cannot recommend it enough. I’ve only read the advanced reader’s copy, but I cannot wait to read the final version once it is released. Here is my review of her book from Goodreads:

This book is both arresting and radical in the gentlest way possible, giving readers the space to become aware of just how desperately our souls are in need of quiet in the chaotic age we find ourselves in. Sarah’s words are an invitation to take even the simplest, tiniest of steps on a pilgrimage towards greater rest for the soul, offering hope that we can taste and see the holy rest God has offered to us in whatever season of life we are in. Some may call her idealistic, or even overly romantic about the power or attainability of quiet in our lives, but such dissmissals are missing the point of her words entirely. Is not the Gospel itself the most romantic and utterly idealistic event in human history, and are we not called to participate in that in every moment of our lives, to long for its full consummation even in this broken world? I encourage you to take Sarahs book deep into your heart, letting it challenge you to pursue a life of reclaiming the quiet God is offering to us in every moment of every day.

A Song

I don’t have just one song to recommend for you this month. Rather, I want to recommend the work of Ophelia Wilde. I first discovered her playlists on YouTube, which are great for studying. Amongst the playlists, she includes some of her own original compositions, which are just lovely. I highly recommend both her albums and her YouTube channel.

Some Artwork

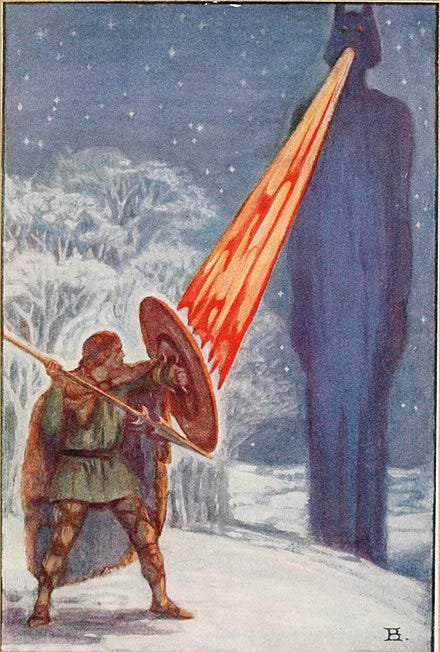

This month, I said goodbye to a beloved family pet: Hershey, the bravest little dachshund there ever was. He reminded me so much of Reepicheep the mouse from The Chronicles of Narnia. Reepicheep’s journey into Aslan’s Country has brought me a little comfort in the wake of Hershey’s final days. This painting, though not of Reepicheep per se, still reminds me of Narnia given the wintry landscape. The piece makes me think of Hershey too, for Hershey simply adored snowy adventures, and you could see the snow wake up his inner wolf heart as he bounded clumsily through the drifts. When I see this painting, it makes me think of those memories.

Proinsias Mac Cana, Celtic Mythology (London: Hamlin, 1970), p. 127.

One of the few truly intelligent writers on Substack, who actually have something to say. I'm very, very happy to have found you and am already looking forward to your next piece.

Reepicheep is my favourite character from the series. His courage heading out in his little boat, over the horizon is such a beautiful last scene. I’m sorry for the loss of your wee dachshund.